PATHOBIOLOGY

The Pathobiology of Membranous Nephropathy: A histologic pattern of many faces

By Dr. Isabelle Dominique Tomacruz-Amante, MD, FPCP, DPSN

Private Practice Nephrologist

Manila, Philippines

Membranous nephropathy (MN) remains one of the most common causes of nephrotic syndrome among non-diabetic adults, with an estimated incidence of 8-10 cases per 1 million. Much of what we know of the pathogenesis of MN comes from the classic Heymann Nephritis (HN) model in the late 1970s. The formation of subepithelial immune deposits occurs in situ when circulating antibodies bind to intrinsic, fixed antigens found on the glomerular capillary wall. Active induction of HN is done by immunizing rats with homologous or heterologous proximal tubular brush border material. Subepithelial immune deposits appear within weeks. On the other hand, passive HN is induced by direct injection of heterologous anti-brush border antiserum, in which case the IgG deposits develop within hours or days. The antigen described here is called megalin, expressed on the surface of rat podocytes. Decades later, studies have found that other native or non-native antigens may also serve as a nidus for the formation of immune complexes or circulating antibody deposition on the subepithelial side of the glomerular capillary wall.

What are key histopathologic patterns for diagnosing MN?

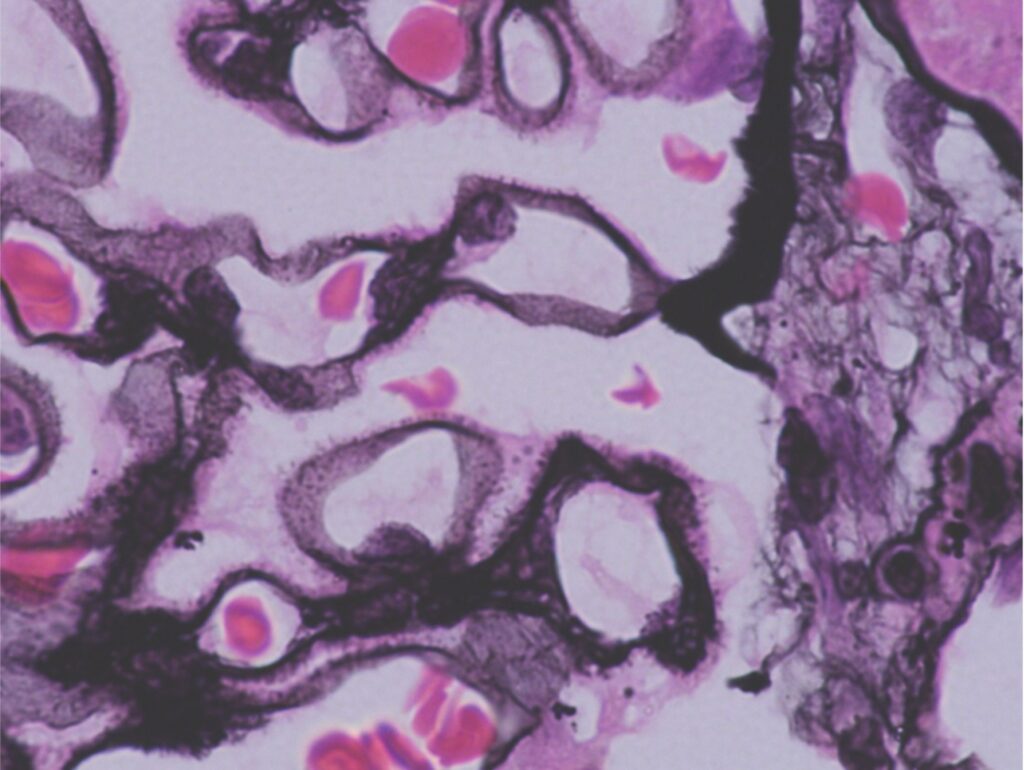

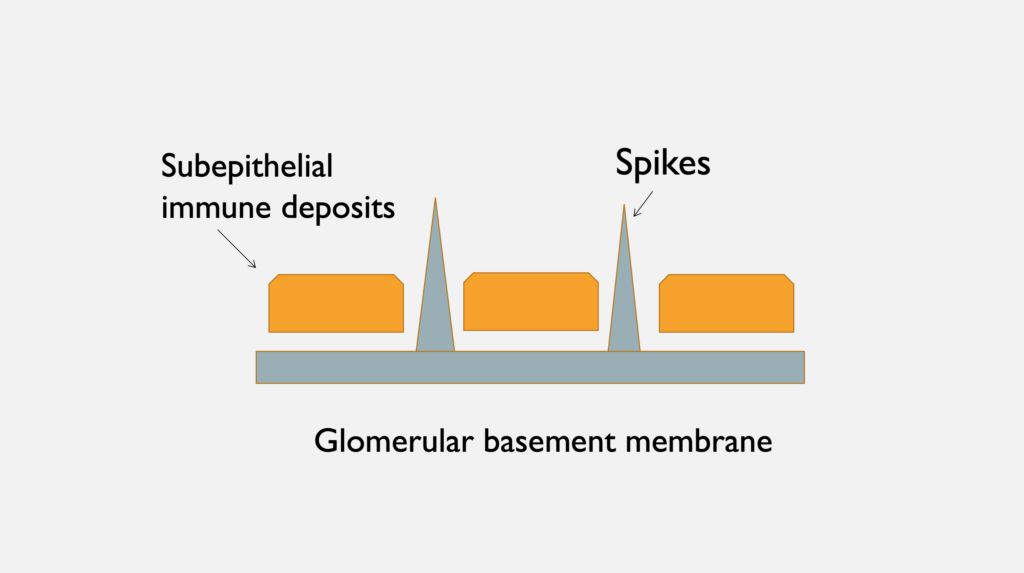

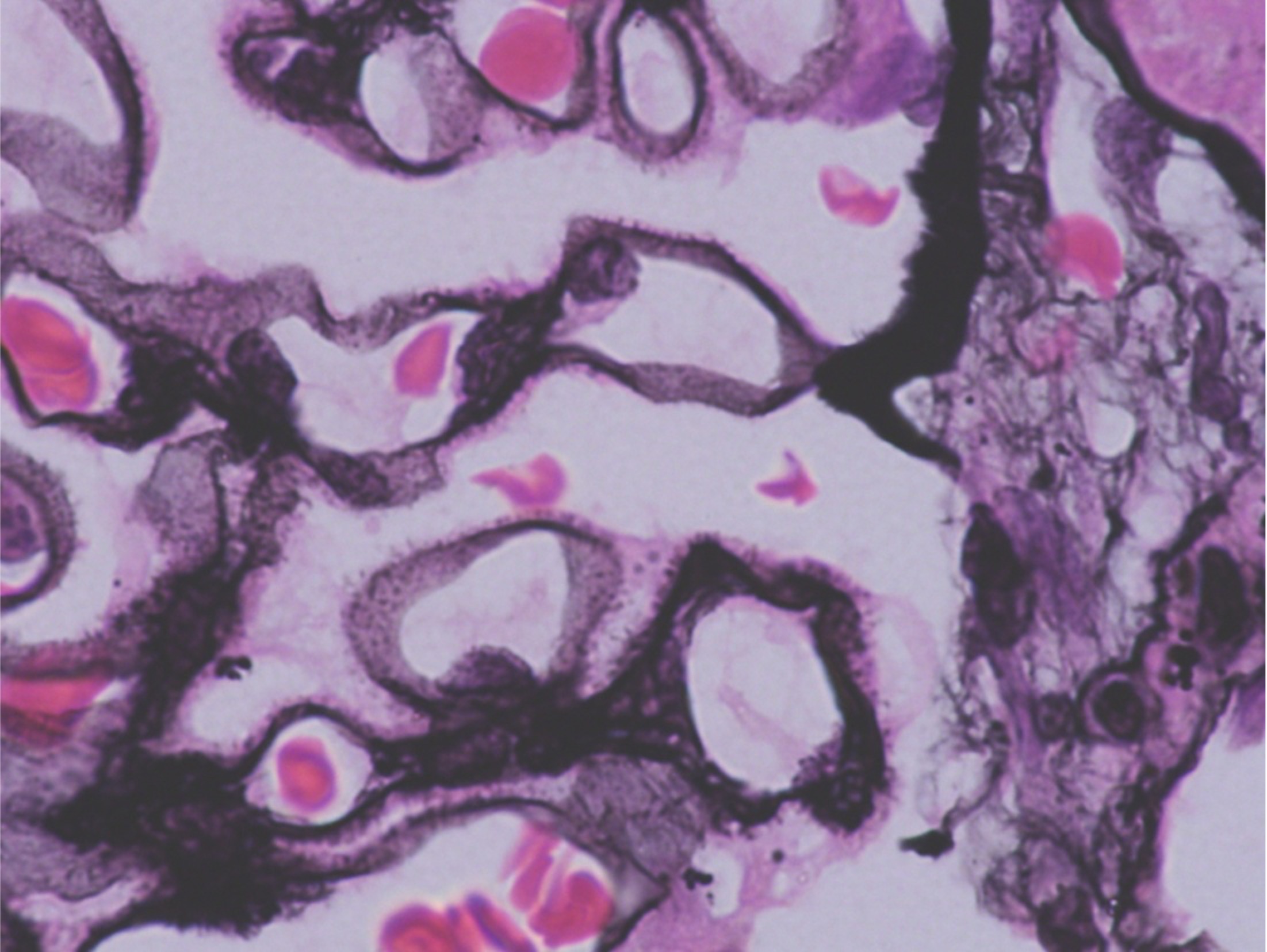

- Diffuse, uniform capillary wall thickening on light microscopy seen on hematoxylin eosin (H&E) or periodic acid-Schiff stain. Demonstration of spikes on Jones silver methenamine confirms MN. Spikes represent the GBM reaction to the subepithelial immune complex deposits.

Early in the course of the disease, the glomeruli may appear normal on H&E but will demonstrate lucencies (craters) on Jone silver methenamine. Craters represent the location of subepithelial immune complex deposits which are as yet unaccompanied by the GBM reaction (spikes). Later on, immune deposits may resorb though the thickened GBM remains.

Figure 1. Spikes on the epithelial side within a thickened glomerular basement membrane (white arrow) on Jones Silver Methenamine. Image courtesy of Dr. Geetika Singh.

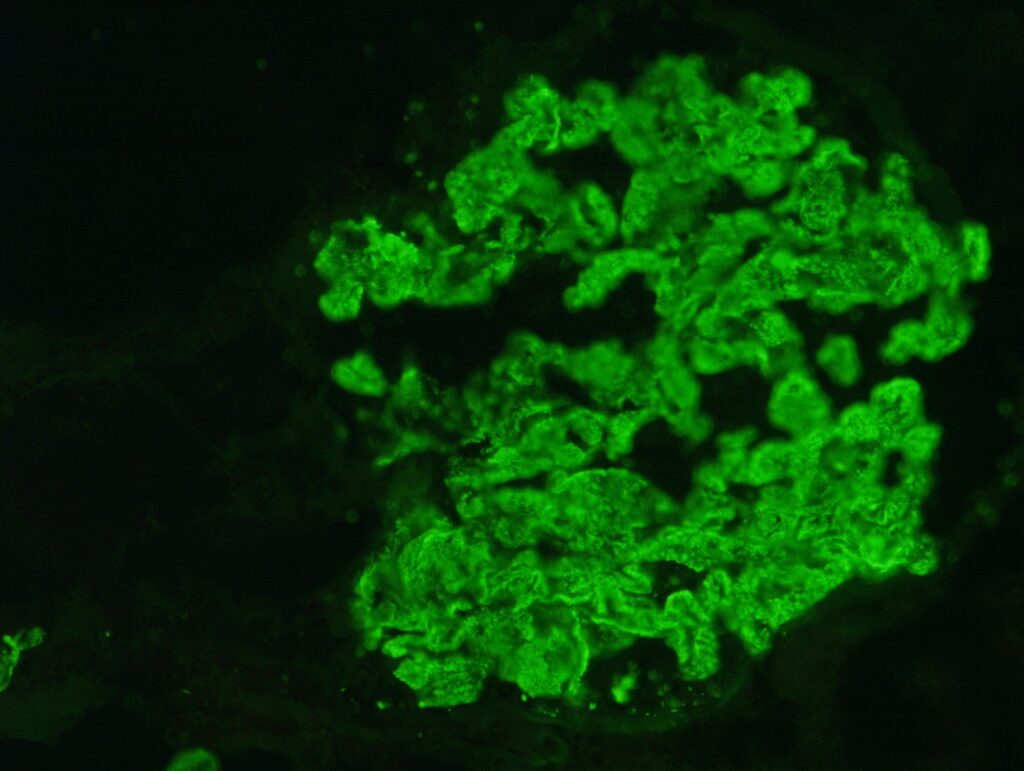

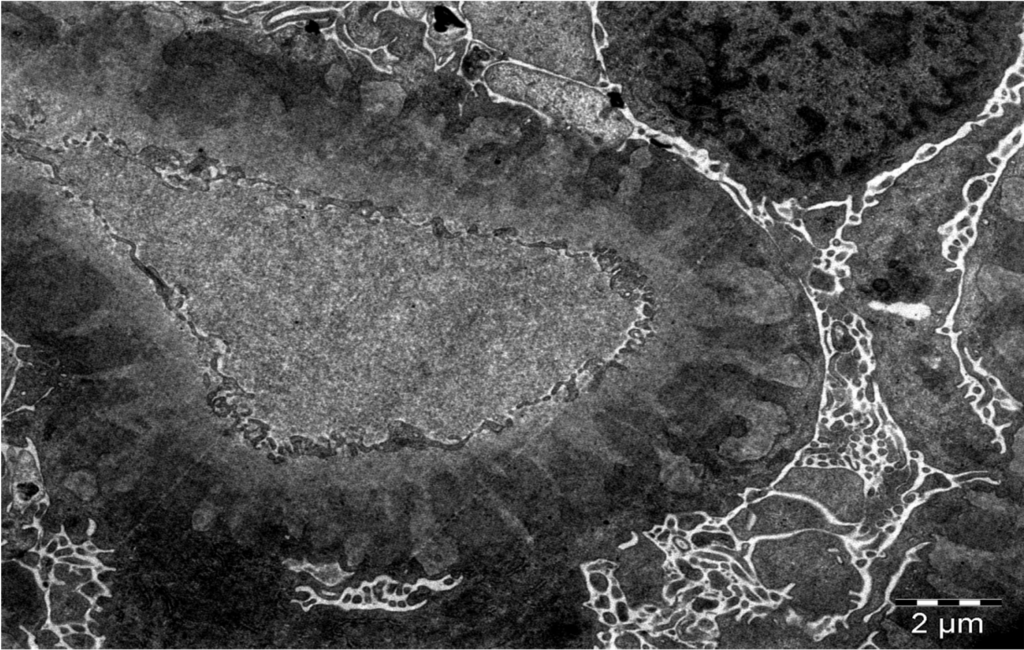

- Presence of immunoglobulin- (typically IgG4 subtype) and complement-containing deposits in the subepithelial position. This is confirmed by immunofluorescence and electron microscopy:

Figure 2. Immunofluorescence shows granular deposits along the capillary wall. Image courtesy of Dr. Geetika Singh.

A

B

Figure 3 A. Electron microscopy shows uniformly spaced, subepithelial, electron dense deposits (white arrows), between GBM spikes (white arrowheads). B. Schematic representation of subepithelial immune deposits and GBM spikes. Image courtesy of Dr. Geetika Singh, with permission.

Despite the presence of complement activation and immune complex deposition, there is usually no associated hypercellularity or proliferation seen since these processes occur on the epithelial side of the glomerular capillary wall.

Other features that have prognostic implications include the presence of segmental sclerosis, and the extent of interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy, all of which may be indicative of progressive disease. The presence of renal vein thrombosis may warrant more urgent therapeutic management.

Are all spikes MN?

The presence of subepithelial immune deposits is strongly suggestive of MN; however, the finding of GBM spikes is not. Some mimics include subepithelial amyloid, which have GBM spicules that look similar to GBM spikes but more closely resemble a cock’s comb or a rooster’s head; another mimic is fibrillary glomerulopathy, which may resemble GBM spikes on silver methenamine or PAS stain, but a closer look on EM will reveal the presence of fibrils.

How is MN classified?

Traditionally, the presence of nephrotic syndrome along with distinct histologic findings on kidney biopsy defined MN. The historical classification typically divides MN into primary or secondary MN:

- Primary MN accounts for 75-80% of patients with MN. It occurs due to an autoimmune response to a normal podocyte antigen in the absence of a secondary cause of disease.

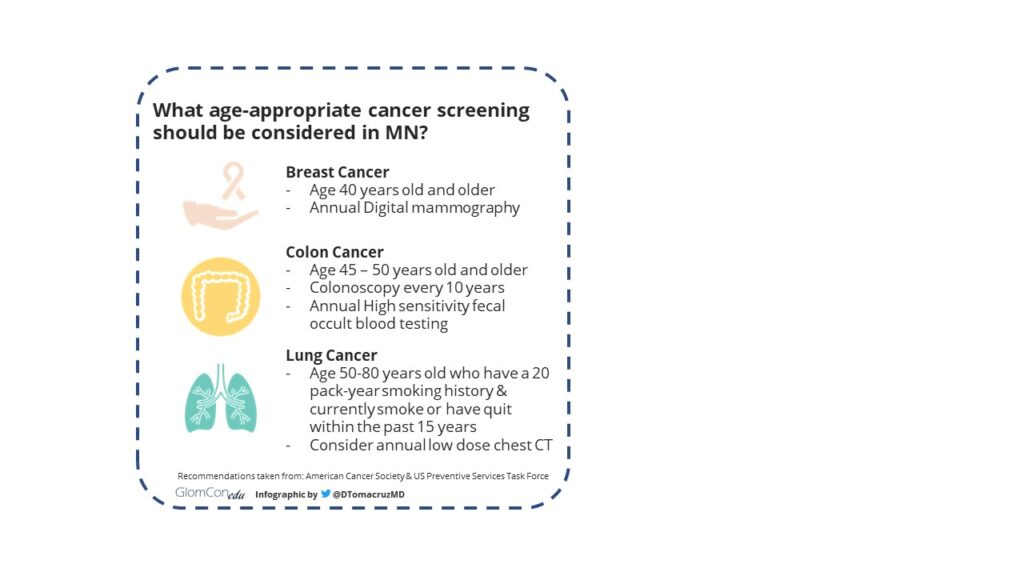

- Secondary MN accounts for roughly 30% of patients with MN, and occurs in the setting of autoimmune diseases, infections, malignancies, or drug exposure. Some common causes include:

- Autoimmune: SLE, mixed connective tissue disease

- Infection: Hepatitis B or C infection, syphilis, malaria

- Drug Exposure: NSAIDs, indigenous medications that contain heavy metals

- Malignancy: breast, colon, lung cancer, Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma

Figure 4. Cancer screening recommendations taken from the American Cancer Society & US Preventive Services Task Force.

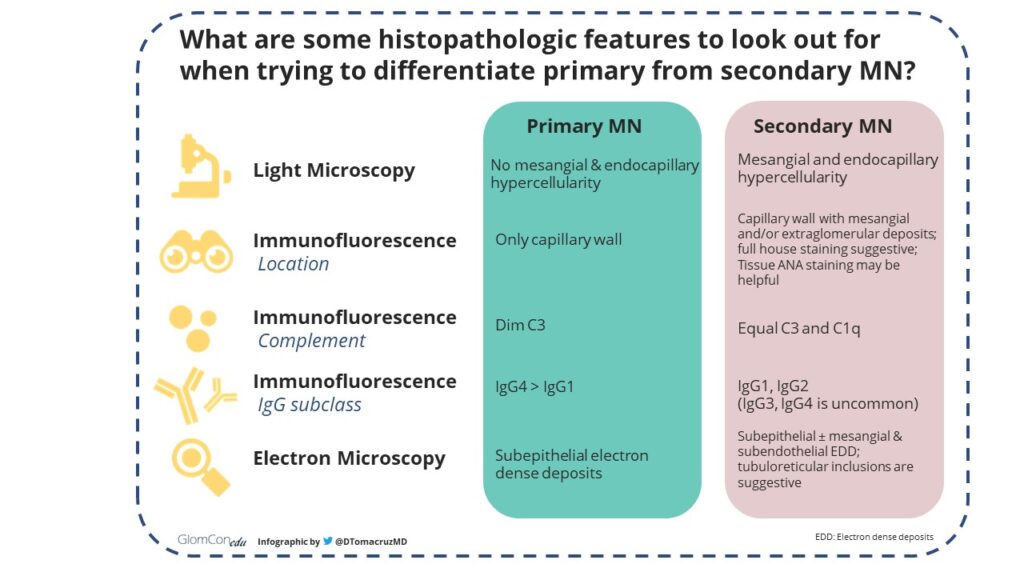

Some key histopathologic differences between primary and secondary MN may be helpful to keep in mind:

Figure 5. Histopathologic features that differentiate primary MN from secondary MN.

Understanding MN as a Pattern of Injury

In recent years, the availability of testing for putative antigens on biopsy specimens and antibodies in serum samples has widened our understanding of the pathophysiology behind MN. In 2002, neutral endopeptidase was found to be responsible for a rare form of alloimmune antenatal MN. This was the first podocytic antigen discovered to cause human MN. In 2009, the M-type phospholipase A2 receptor (PLA2R) was identified as a target antigen in a majority of primary and otherwise ‘idiopathic’ MN. This paved the way for the discovery of many other antigen-associated MN responsible for distinct disease entities. The classification of MN as primary and secondary has since been challenged. Membranous nephropathy is now described as a pattern of glomerular injury, and, strictly speaking, is a clinical-pathologic diagnosis that may be caused by a variety of diseases. In recent years, we have been learning that each ‘new’ antigen that causes MN carries a distinct set of clinical and pathologic characteristics specific to the antigen and should be labeled as specific disease entities.

Antigen-associated MN

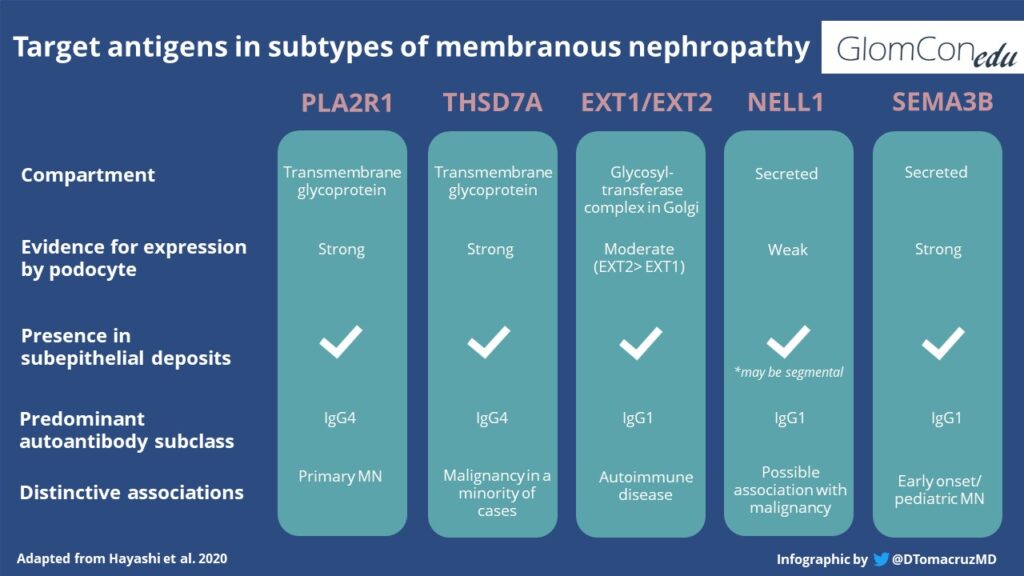

The most common target autoantigens described to date is PLA2R, which is expressed by human podocytes. Circulating anti-PLA2R antibodies were found to be responsible in 70-80% of patients with primary MN. The use of this serologic assay for diagnosis has precluded the need for kidney biopsy in some cases. For several years, proteinuria and elevated serum creatinine have also been the only markers of disease severity, but now, several studies have shown that high titers of PLA2R antibody may also correlate with a higher risk of nephrotic syndrome, end-stage kidney disease, and lower risk of spontaneous remission.

The recent KDIGO Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Glomerular Diseases suggests that in clinical practice, it is useful to assess the risk of disease progression with a combination of clinical and laboratory factors, and the use of PLA2R antibody. PLA2R Antibody level greater than 50 RU/mL is a suggested cut-off for MN with a high risk of disease progression, although this is not validated.

There is growing interest in the study of specific antigens involved in MN. Those recently described include THSD7A, neural epidermal growth factor-like 1 (NELL-1; ⅓ of which are associated with malignancy), semaphorin-3B, and exostosin 1/ exostosin 2 (usually associated with lupus nephritis). With regards to exostosin 1 and 2 specifically, there is debate about whether they truly represent MN antigens or if they are a biomarker of disease severity. The use of laser microdissection and tandem mass spectroscopy have also aided in the discovery of novel antigens among PLA2R-negative MN. A comparison of target antigens in some types of antigen-associated MN is found below:

Much progress has been made in the past two decades with the identification of multiple target antigens in membranous nephropathy, the development of assays to detect and monitor disease. Perhaps in the near future, we may also see progress in the development of antigen-specific therapies with fewer side effects.

Take Home Points:

Membranous nephropathy displays heterogeneity in pathology and etiopathologies, and is a clinico-pathologic diagnosis describing a pattern of injury and not a specific disease per se. Diagnosis requires an in-depth investigation to ascertain the cause. The discovery of target antigens in membranous nephropathy is still evolving and has the potential for individualizing care and change the landscape of diagnosis and management for this complex disease.

Disclaimer: Dr. Tomacruz-Amante reports no conflict of interest.